The following is an article from the New Zealand Herald dated 22nd Apr 1893

The Church and the drink traffic

In the heart of Sussex, on an eminence commanding view of some of the most beautiful landscapes in England, stands a wayside inn kept by a clergyman of the English Church. One of the representatives on an English paper recently spent a week at this inn, and thus narrates his experience:-

The Anchor stands at the top of Scaynes Hill on the old turnpike road from Lewes to London. In a garden patch in front of it is a very old cedar tree, which is a landmark for miles around. To the trunk of this old tree is fastened with iron bands an old ship’s anchor, the sign of the inn. The west windows command a view of beautiful meadows sinking and rising till they reach the South Downs. To the south may be seen the roads meandering towards Lewes, and through a break in the Downs Newhaven is occasionally discernible, sixteen miles away. From the eastern windows stretch acres of oak-forest land, a country throughout which the inhabitants still use Saxon words which have come down the ages with unbroken continuity. The shriek of the railway whistle never reaches Scaynes Hill and a newspaper is rarely seen at the Anchor.

The tap room was full one Saturday night. A grey haired old shepherd, in smock frock, sat in the old-fashioned chimney corner smoking his clay, sipping his ale, and with bucolic solemnity contemplated the burning logs on the broad hearth stone. He never spoke. The politician who was present did – unceasingly. He and a tall gamekeeper had an hour’s argument on the rights of property. The wit of the company was a fat little waggoner called Punch, who was the moving spirit of a half-dozen who played “shove’a’penny” on the table-end all evening.

Altogether there were a rough lot, good-humoured, but capable of mischief if annoyed. The manager, Joshua Hill, told me that the first night he opened the company came to him bent on a row. “‘Ere, mister,” said one, “you’ve to come and sing us a song.” He went into the tap-room, stood upon a bench, and sang “The Anchor’s Weighed.” The whole company joined in the chorus. Even the old shepherd looked up from his corner and piped a note, henceforth the new manager was accredited a good fellow. That the house is a moral success there can be no denying. The success lies in that rather than a village public house it is a village club. There is a room with some old illustrated papers, cards, dominoes, draughts, etc., where the rising generation mostly congregate and play games and drink coffee. The curate of the parish often spends and hour in this room initiating some of the young men into the mysteries of chess. In the orchard is a good quoit ground, much used in the summer. There is, too, a cricket team connected with the Anchor. They practise on the village common, and play their matches in one of the vicar’s fields. For visitors who come to stay there is a sitting-room furnished with old oak. The bedrooms, which I was informed are to be extended, have small windows and low ceilings. They are nevertheless pleasant to sleep in, and pleasant to awake in, for the air that comes through, with the voices of birds in the morning, is the freshest and purest. During the morning I strolled through the neighbourhood, and had

An interview with the vicar

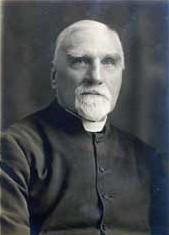

The Rev. Frederic Willett is a man in the fifties, with a healthy, jovial face, a beard of American cut, and no suspicion of the bigot or the faddist about him. He is simply a wealthy gentleman with a love of country life, tempered with a knowledge of human nature gained by many years’ parochial work in manufacturing towns. Scaynes Hill is his own property, owning many square miles of beautiful country, and one of his nearest and most influential neighbours is Mr. Justice Grantham. His home is a romantic mansion named Cudwell, “pronounced Cuddle,” said a merry minx of whom I asked the way. At “Cuddle” I found the rev. gentleman. His rooms have polished oak floors and wainscots. Mr. Willett is a lover of antique in furniture, and his house contains some costly Chippendale.

“I have always loved the country,” he said, “but for many years I laboured among the miners and ironworkers of West Bromwich and Wolverhampton. There I saw what convinced me that a properly conducted public house is a greater power towards temperance than is the teaching of teetotalism. Eleven years ago I came here and settled down on my estate. During these eleven years I have conducted the parish of Scaynes Hill without any fees whatever. I have kept all the workmen on my estate employed winter and summer at 18s a week, and have reduced the cost of living to the villagers. I am a farmer, market gardener, and publican. This last winter I have killed my own cattle, and supplied the villagers with meat at a lower rate than the butchers did. When I came here the bucolic demoralisation was extreme. The villagers drank, swore, blasphemed and quarrelled, not knowing any better. The Anchor was a source of trouble to me. About twelve months ago the lease expired. I had the place cleaned and repaired, and put in my own manager. Drunkenness has since almost ceased, and there is now neither poverty nor sickness in the parish.”

“But how is this philanthropy to be accomplished elsewhere? I don’t claim to be a philanthropist. I want you to understand that I’ve made the business pay in all departments. The public house used to bring me a rental of £29 a year; now I pay myself £40 a year from it. I mean to make it pay better still. I am planning to lay out fifty acres of woodland at the rear of the Anchor, with drives, walks, and pleasure gardens, and hope to attract visitors in the summer time.”

Asked if his model was being copied elsewhere, Mr. Willett said several people had been over to see the place, and Mrs. Meynell Ingram, of Hoarcross, Burton-on-Trent, had just opened a public-house on the same principle.